Overview:

As part of the seminars I attended and also during my training as a “Heilpraktiker für Psychotherapie”, I came into practical contact with some selected tools, including:

- Solution-oriented short-term therapy according to Steve de Shazer

- Client-centered therapy according to Carl Rogers

- Resource oriented approaches

- Mindfulness and breathing techniques

- Definition of goals

- Nonviolent communication according to Rosenberg

- Progressive muscle relaxation according to Jacobson

There are a variety of approaches to support people psychologically. I don't want to give a comprehensive overview at this point. With kind permission I refer you to this source. Of all the existing movements, I like the mindfulness-based and humanistic approaches the most (see here). They form the core of my work.

I have the attitude that everyone who comes to me already knows the solution to their problem within themselves and takes this knowing in the session. My role is to encourage the emergence of what Rogers calls „actualizing tendency“. Among other approaches, I do this by carefully mirroring and reflecting on what you bring to the sessions.

The foundational principles of my work are discretion, authenticity, empathy (empathetic understanding) and appreciation, no matter where you stand and are right now. I consider it essential to encounter clients on an “eye level” – from human to human.

The body, the breath and Awareness

For a couple of years now my own breath increasingly draws my attention. There is much usefulness in looking more carefully at this phenomenon...

The breath has long been seen as a link between the material world, i.e. the human body and the mind / psyche (M. Stein, „C.G. Jungs Landkarte der Seele“, Patmos, 1998). This is reflected in several words from different languages:

- Ancient Indian prana → physical breath, air | essence of life;

- Chinese Chi → natural air | Life energy, Japanese Ki;

- Greek pneuma → air, breath | spirit, life essence;

- Greek phren → diaphragm | Spirit;

- Hawaiian ha (in aloha) → spirit | wind, air | Breath;

- Jewish ruach → breath | creative spirit;

- Latin spiritus → breath | Spirit

Likewise in the Slavic languages, spirit and breath have the same linguistic roots.

Ernst Andreas Stadter writes: "Is it flat, heavy, light, calm, rushed? The breath says a lot, basically everything about my current state of mind. That is an ancient wisdom of many peoples and cultures." (E.A.Stadter, „Ich will dir sagen, was ich fühle“, Herder Verlag, Freiburg, Basel, Wien, 1996) The psychiatrist Wilhelm Reich ( † 1957) has in this context made an interesting observation: he thought he had recognized that psychological resistance and defense mechanisms are related to restricted breathing. This was confirmed by Stanislav Grof, a Czech psychiatrist. (S. Grof, Der Weg des Psychonauten Band 1, Nachtschatten Verlag, 2019, S. 360)

Mijares and Bessel van der Kolk also write about this analogously: “You can see your physical and emotional state by observing your breathing rhythm, and you can change this state by changing your breath. […] As you become aware of your breath, you also become aware of the interaction between your inner state and your surroundings” (Sharon G. Mijares, The Revelation of the Breath A Tribute to Its Wisdom, Power, and Beauty , State University of New York Press, Albany, 2009, p.241). A modern finnish study confirms this further: “Prior work suggests that voluntary reproduction of physiological states associated with emotions, such as breathing patterns or facial expressions, induces subjective feelings of the corresponding emotion.” (L. Nummenmaa et.al., Bodily maps of emotions, Psychological and Cognitive Sciences, 2013, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1321664111) And B. van der Kolk writes: “… scientific methods have confirmed that changing breathing can alleviate problems with anger, depression and anxiety” (B. van der Kolk, The Body Keeps the Score, Penguin Books, UK, 2014). And again the finnish study: “Similarly, voluntary production of facial expressions of emotions produces differential changes in physiological parameters such as heart rate, … finger temperature, and muscle tension, depending on the generated expression. However, individuals are poor at detecting specific physiological states beyond maybe heart beating and palm sweating.” That is exactly where mindfulness/awareness comes into play, but more on that later.

In the western culture, Wilhelm Reich was one of the first to integrate the body and breathing into psychotherapy (disclaimer: The counceling I offer is no psychotherapy according to the “Psychotherapeutengesetz”). And he was one of the first to recognize the connection between body tension/ rigidity and psychological problems. Among other things, the various body psychotherapies emerged from his discoveries.

His main thesis is that the body accumulates and holds tension in the muscles, and in some cases simultaneously restricts breathing, to unconsciously protect us from unwelcome emotions. (see above, The Revelation of the Breath, p.73) He divided the body into different areas and assigned each a more or less separate meaning: for example, emotions such as desire, heartache, anger and sadness are said to be stored in the chest area. Sadness can also occur in the throat area (this is also confirmed in the Finnish study from 2013: L. Nummenmaa et.al., Bodily maps of emotions, Psychological and Cognitive Sciences, 2013, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1321664111). If the larynx/ throat region feels contracted for a long time, this could indicate that sadness and tears are being held back excessively in a way that is no longer useful. In such a case, Reich instructed to relax the neck and jaw and to breathe more deeply through the open mouth. As a body psychotherapist, he can overcome psychological resistance and the released and freed emotions lead to noticeable relief.

Reich observed that many people, sometimes unconsciously, have a very limited breathing pattern. For example, shallow breathing, about ten times per minute into the upper part of the lungs (hardly any abdominal breathing), is common. This type of breathing, so to speak only in the chest area, is not natural (see above, The Revelation of the Breath, p.45). Relaxed, natural breathing takes place predominantly in the abdominal cavity. Babies and animals intuitively have natural breathing (“Diaphragmatic breathing”, you can google that =) e.g. https://www.va.gov/WHOLEHEALTHLIBRARY/tools/diaphragmatic-breathing.asp). A shallow breath only exchanges around half a liter of air in the lungs (≈15%). The result is a low oxygen supply to the brain and the remaining organs, which can result in fatigue, loss of vitality and the ability to concentrate.

It is assumed that the unconscious purpose of limited breathing is to limit self-expression. Something must not or should not be shown or felt. Full perception and feeling is then restricted. Under certain circumstances, as a child, in the environment at the time, this limitation made sense and was even necessary for survival. As an adult, however, it is often a hindrance and no longer useful.

Below you can find a short bioenergetic exercise (a form of body psychotherapy). Anyone who is interested is welcome to try it out.

- Place your hand on your chest and breathe in and out naturally. Notice how your chest feels. Stay with the feeling for a while.

- Next, remove your hand from your chest and place your pinky finger on your belly button while the rest of your hand rests on the stomach area above your belly button below your chest. Breathe in and out, noticing how that stomach area feels under your hand. Stay with the feeling for a while.

- Finally, place your thumb on your belly button and let your hand rest on the stomach area below. Breathe in and breathe out. Feel this area too.

- Focus your attention on breathing and observe which of the three areas described above moves the least while inhaling. The area of least movement indicates an area of “blocked energy.”

- Place your hand on the area that is most restricted and increase or deepen your breathing. If this is difficult, experiment with how far you want to go.

Breathing is a bodily process that can generally occur consciously or unconsciously. Conscious modification of the breath is used in many spiritual practices, such as the ancient Indian pranayama breathing exercise, Kundalini Yoga, Siddha Yoga, the meditation of the Burmese Buddhists and Sufi practice.

I have been practicing Vipassana Meditation as taught by S.N. Goenka for some years now. The first step in this form of mindfulness meditation is the conscious observation of your own breath (Anapanasati; from the Pali anapana=breath in and out and sati=mindfulness, literally "mindfulness of breathing"). It is not changed, but left naturally, as it is. If it is fast, then it is fast, if it is heavy, then it is heavy... Similarly, the described body psychotherapies also include the conscious observation of the natural breathing process. Compared to the above spiritual practices, the modification of the breath at will is NOT part of anapanasati.

Essentially two abilities are trained: on the one hand, the "faculty of awareness" (latin facultas "ability"). On the other hand, it is practiced not to react mentally to what is perceived (exercise of equanimity = equanimity ≠ indifference).

The body position is an upright sitting, as comfortably as possible (e.g. on a chair). The back should be straight and the rest of the body relaxed. The eyes remain closed. As soon as a distraction occurs in the form of a feeling or thought - e.g. after five minutes you realize that you were "somewhere else" - you return to the breath. Thoughts are not pursued during practice, they are allowed to come and go, arise and die away, without being attached to them.

Again: Thoughts are allowed to arise and be there, the training is just to not cling to them, "follow" them. From another perspective, it is about intentionally bringing attention to the present moment without evaluating what is showing up in the present moment. If ratings and judgments occur, it is important to become aware of them and not "get caught up" in them, e.g. by mentally "sticking to them". Jack Kornfield says it is like with a puppy dog: you train him again and again to come back. (okay, enough metaphors :-)

The focus remains on the (natural) breath throughout. The exit of the nostrils, for example, can be used as an aid. One can observe the flow of air and the sensations there on the inner walls of the nose. "When I breathe in, I'm aware that I'm breathing in. When I breathe out, I am aware that I am breathing out.” This is a sentence that has often helped me during practicing.

In a second step of Vipassana meditation, attention is shifted, and the sensations throughout the whole body are systematically focused (body scan). Here, too, it is about consciously perceiving without reacting mentally.

The systematic practice of mindfulness (methods) is part of many counseling and therapeutic approaches (e.g. MBSR or Acceptance and Commitment Therapy from behavioral therapy). It is an essential part of my work.

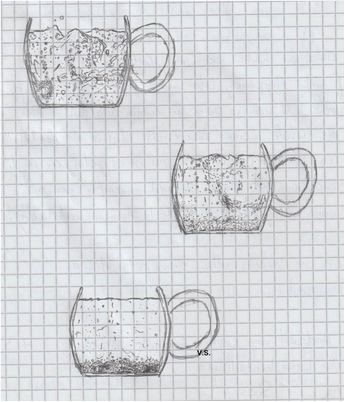

It is in the nature of things that we have a tendency to seek fulfillment in the "outside", in the material world. Buddhism emphasizes that this can only be sought (and found?) “inside”. The power of the breath is counteracting this inherent tendency in us. The practice of keeping your attention on the natural breath calms the mind. I find two analogies very apt here: the mind/mental state as water e.g. a calm forest pond under a full moon. When everything is calm, even the rarest animals come out of their hiding places to the water. Another metaphor is a cup with dirty water swirling around in it. In the course of the meditation, the liquid clears and the dirt (= thoughts) settle:

After a little practice, the result is most often more serenity, stability and clarity. Qualities that strengthen with regular practice and also show up outside of formal meditation. Irritability and nervousness and a calm state of mind are mutually exclusive. The latter is often the prerequisite for any successful psychological intervention/measure.

To round off, I want to clarify: the practice of meditation is something I have experience with. It helped me a lot. That is not to say that this is the appropriate method of choice for everyone. There is an uncalculable number of tools and methods to achieve more clarity and minimize mental suffering. It is up to you to decide which approach is the right one for you.

"In order to heal we need to touch with love that, what we previously touched with fear."

Stephen Levine

Disclaimer:

The counceling I offer is no psychotherapy according to the “Psychotherapeutengesetz”. My work does not replace a doctor or a psychiatrist. In the event of serious crises or acute suicidality and in emergencies, please call the “Oberbayern Psychiatry Crisis Service” around the clock on 0800 655 3000 or the emergency services (No. 112). In Vienna this is the number 01 31330 around the clock.

Alternatively (all free of charge):

Telephone counseling: 0800 1110111 (Protestant) 0800 1110222 (Catholic)

Telephone counseling for children and young people: 0800/1110333

Info Telephone Depression: 0800 3344533